2c Web Scraping

Learning Objectives

- Understand when web scraping is appropriate vs. using APIs

- Navigate the legal and ethical landscape of web scraping

- Parse HTML structure and extract data using BeautifulSoup/rvest

- Handle pagination, rate limiting, and dynamic content

- Build robust, respectful scrapers for research data collection

Before You Scrape: Legal and Ethical Obligations

Web scraping exists in a legal gray area. What's technically possible isn't always legal or ethical. Before scraping any website, you must understand the legal framework and respect website owners' rights.

This module teaches responsible scraping for legitimate research purposes only.

Table of Contents

2c.1 When to Scrape (and When Not To)

Before writing a single line of scraping code, you need to ask: is scraping actually the right approach? Scraping should be your last resort, not your first instinct. Let's see why.

🔍 Applying This to Our Project

For our CO2 emissions data, let's check alternatives first:

- Check for existing datasets: We already used the World Bank API for CO2 data in Module 2b. Wikipedia offers additional historical data and different aggregations we can complement our dataset with.

- Check for an API: Wikipedia has a MediaWiki API that can retrieve page content. However, parsing HTML tables is often easier than parsing wikitext.

- Why we scrape anyway: This is a learning exercise. Wikipedia's tables are well-structured, legal to scrape, and let you practice techniques you'll need for sites that don't have APIs.

The Hierarchy of Data Acquisition

Always prefer these options in order:

- Official datasets — Published data files from the source

- APIs — Structured, sanctioned data access (see Module 2b)

- Data request — Contact the organization directly

- Web scraping — Last resort when above options fail

Scraping has real costs:

- It's fragile: If a website changes its layout, your scraper breaks

- It's slow: Polite scraping requires delays between requests

- It's legally murky: APIs and official datasets have clear usage terms

- It requires maintenance: You'll spend time fixing broken scrapers

2c.2 Legal Framework

You've decided that scraping is necessary for your project. Before writing any code, you need to understand what you're legally allowed to do. This section might seem like a detour from the technical content, but skipping it could put your research—and potentially your institution—at risk.

🔍 Applying This to Our Project

For our Wikipedia CO2 emissions scraper, we're in an excellent legal position: Wikipedia content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license, which explicitly permits reuse. Their robots.txt allows scraping of article pages. We just need to be polite (rate limit our requests) and provide attribution if we publish the data.

I Am Not a Lawyer

This section provides educational information about legal concepts related to web scraping. It is not legal advice. Consult with your institution's legal counsel or a qualified attorney for guidance on specific situations.

Key Legal Considerations

The legal landscape for web scraping involves several overlapping frameworks. Click each topic below to expand the details.

Most websites have Terms of Service that may prohibit automated data collection. Violating ToS can result in:

- Being blocked from the website

- Civil lawsuits for breach of contract

- In some jurisdictions, criminal charges under computer fraud laws

Before scraping, find and read the website's ToS. Look for keywords like "automated", "scraping", "crawling", "bot", "data collection".

The robots.txt file tells automated systems which parts of a site they can access. It's located at the root of every website (e.g., example.com/robots.txt).

Technically, robots.txt is a voluntary standard. However, ignoring it demonstrates bad faith and may be used against you in legal proceedings. Always respect robots.txt.

Even if you can legally access data, you may not have the right to use or republish it:

- Copyright protects creative works (articles, images, unique descriptions)

- Database rights (EU) protect substantial investments in compiling data

- Facts themselves are generally not copyrightable, but their presentation may be

The CFAA prohibits "unauthorized access" to computer systems. Recent court decisions have clarified researchers' rights:

- hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn (2022): Scraping publicly accessible data is not "unauthorized access." Landmark decision for researchers.

- Van Buren v. United States (Supreme Court, 2021): Violating Terms of Service alone does not trigger criminal CFAA liability.

- Sandvig v. Barr (2020): CFAA does not criminalize mere ToS violations for research purposes.

The EU Digital Single Market Directive 2019/790 created explicit protections for research scraping:

- Article 3 (Research Exception): Research organizations may perform text and data mining regardless of contractual terms. This overrides ToS restrictions for legitimate research.

- Article 4 (General Exception): Any lawful access holder may perform TDM unless the rightsholder has explicitly reserved this right in machine-readable format.

GDPR considerations: Article 89 allows processing personal data for research with appropriate safeguards (data minimization, pseudonymization).

- AI Training Data Debates: Academic research maintains stronger fair use protections than commercial AI training

- US Copyright Office (2023): Factual data extraction generally does not constitute copyright infringement

- EU AI Act (2024): Research scraping for AI development has explicit carve-outs

- Meta v. Bright Data (2024): Reinforced that scraping public data does not violate the CFAA

Legal protections vary by country. EU researchers generally have stronger statutory protections. Consult with legal counsel about which framework applies to your specific project.

Research-Specific Considerations

Pre-Scraping Checklist for Researchers

- Check for existing datasets — ICPSR, Harvard Dataverse, Kaggle, data.gov

- Check for an API — Even if undocumented, try adding /api/ to the URL

- Read the Terms of Service — Document that you checked and your interpretation

- Check robots.txt — Respect all directives and document compliance

- Consider fair use/TDM exceptions — Is your use transformative? Non-commercial? Does EU Article 3 apply?

- Contact your IRB — Human subjects data may require approval

- Consult your institution — Many universities have policies on scraping

Documentation Template for Research Scraping

It's a good idea to create a dated memo that includes:

- Research purpose: What question are you investigating? Why is web data necessary?

- Data source assessment: Did you check for official datasets, APIs, or data request options?

- Legal analysis:

- ToS review: What do the terms say? How does your use comply or qualify for exceptions?

- robots.txt review: What does it permit/prohibit? How will you comply?

- Applicable law: Which jurisdiction applies? What protections exist (CFAA/hiQ, EU TDM)?

- Ethical considerations: Is the data sensitive? Could individuals be harmed? What safeguards will you implement?

- Technical safeguards: Rate limiting, caching, minimal data collection, secure storage

- Institutional approvals: IRB status, departmental sign-off, legal consultation

Keep this document with your project files. If questions arise years later during peer review or legal inquiry, this contemporaneous record demonstrates good faith.

2c.3 Understanding HTML Structure

Now that you understand when and whether to scrape, it's time to learn how web pages are structured. This is the foundation of all scraping work. You can't extract data from a page if you don't understand where that data lives.

Think of a web page like a document with a very precise organizational system. Just as a research paper has headings, paragraphs, tables, and footnotes, a web page has HTML elements that organize its content. Your scraper's job is to navigate this structure and extract exactly what you need.

🔍 Applying This to Our Project

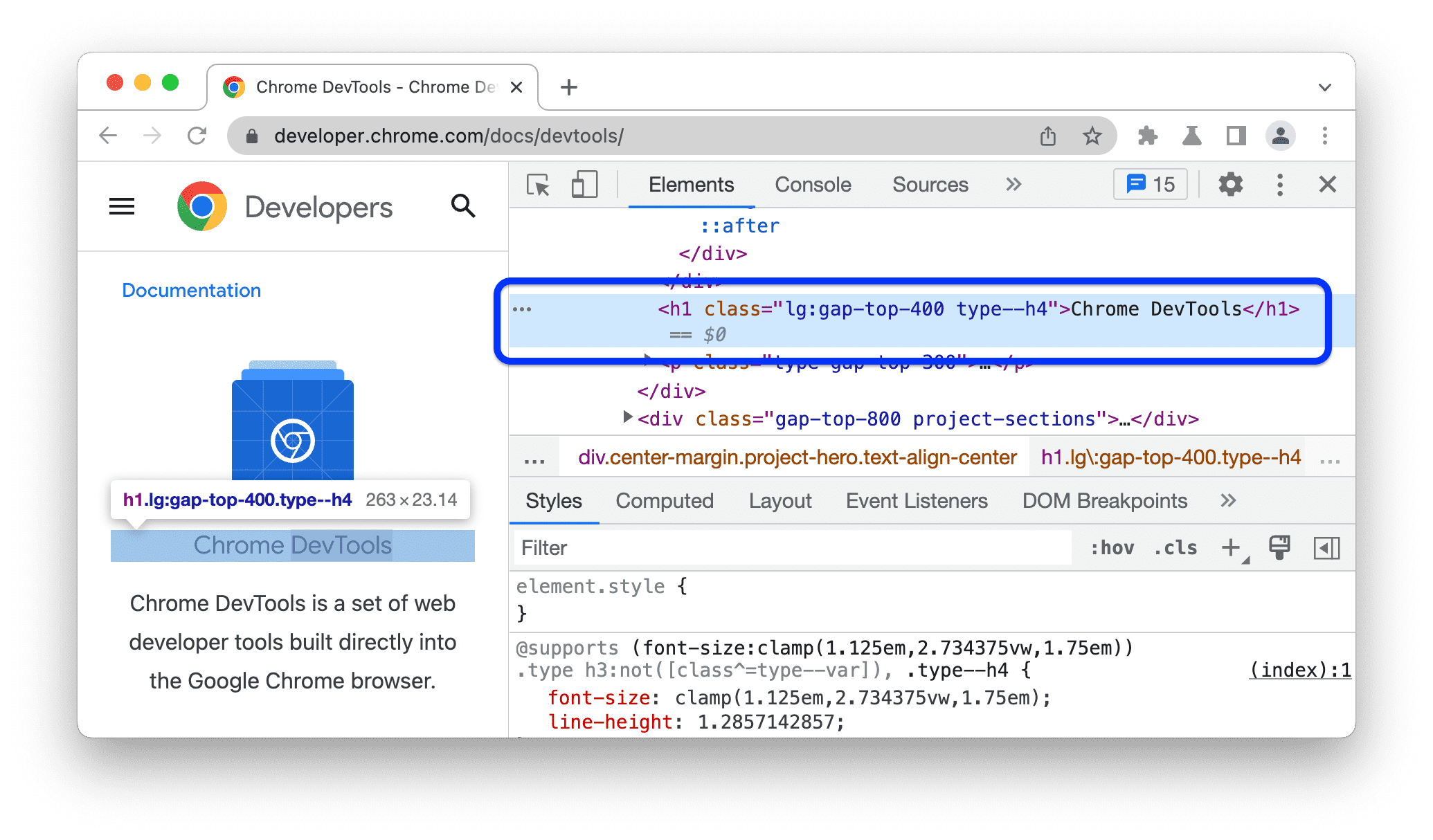

Visit the Wikipedia CO2 emissions page and right-click → Inspect on the data table. You'll see it's a <table> element with class wikitable. Each row (<tr>) contains cells (<td>) with country names and emissions data. This structure is what we'll target with our scraper.

What is HTML?

HTML (HyperText Markup Language) is the structure of web pages. It uses nested tags to organize content. To scrape data, you need to understand this structure so you can tell your code where to find the information you want.

HTML Elements

HTML is made of elements—building blocks that contain content. Every element has the same basic structure:

Attributes: class and id

Attributes help identify specific elements. The most important for scraping are:

- class — Shared by multiple elements (e.g., all prices might have

class="price") - id — Unique identifier for a single element (e.g.,

id="main-content")

Viewing Page Source

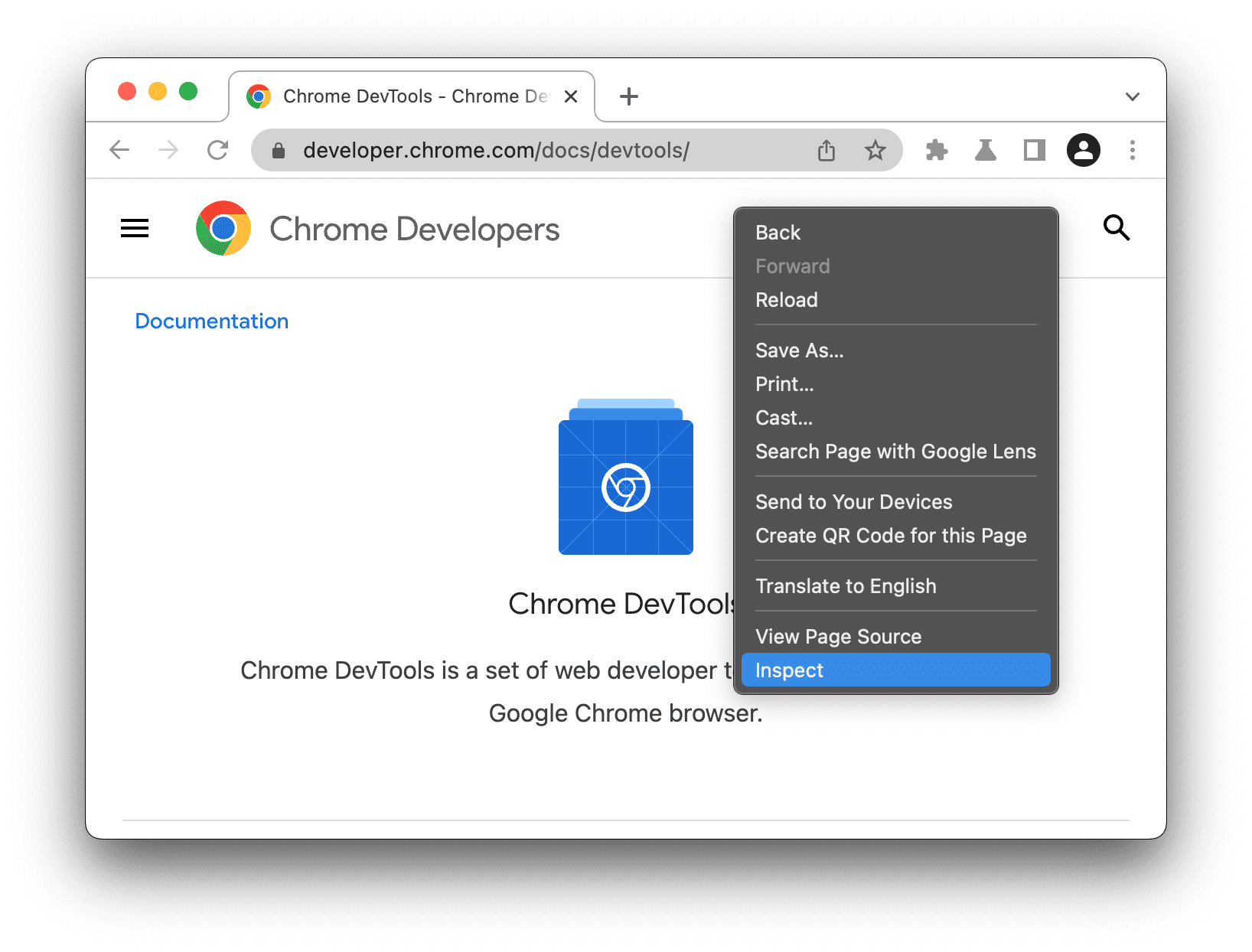

To see a page's HTML structure:

- Right-click anywhere on the page

- Select "View Page Source" (sees original HTML) or "Inspect" (interactive developer tools)

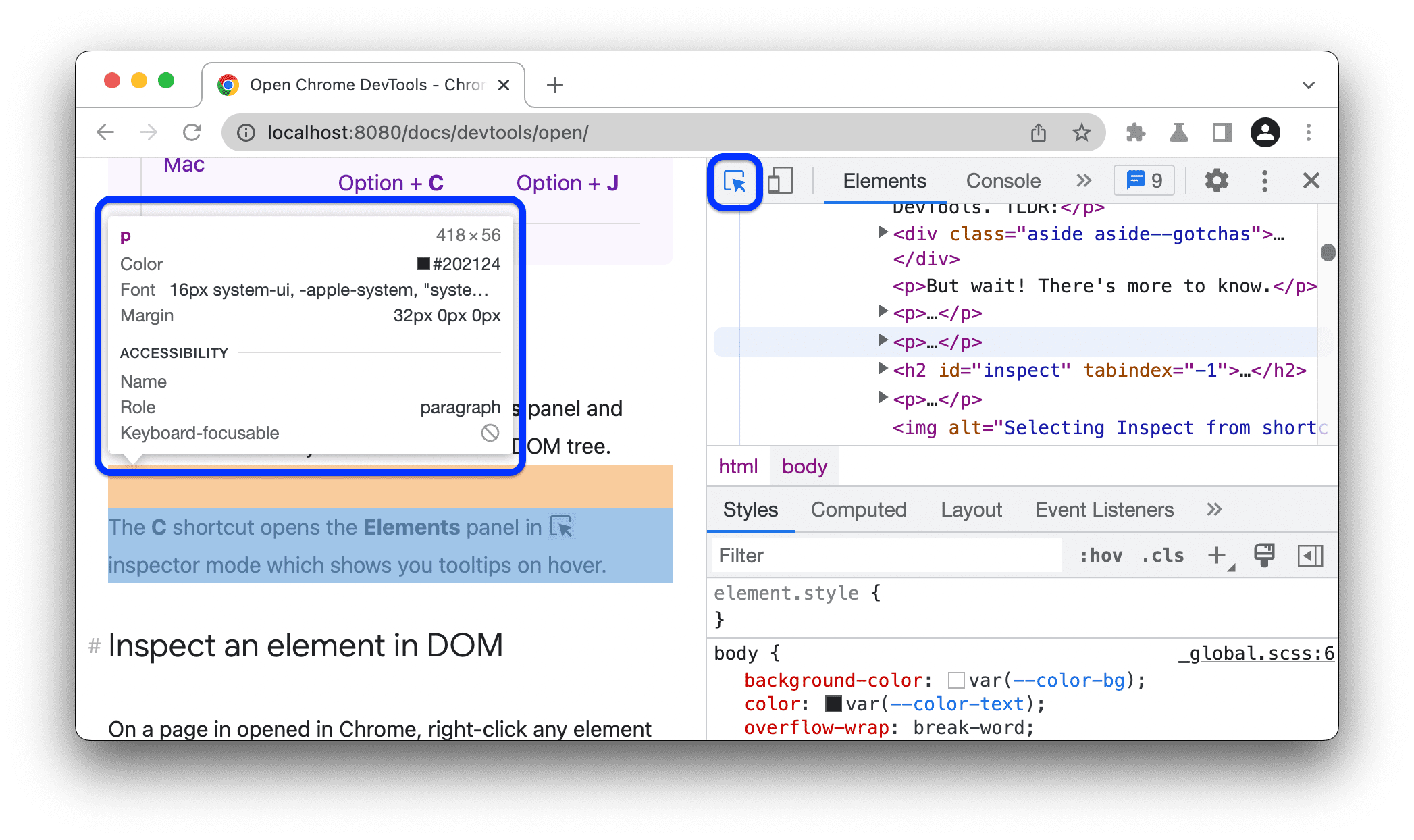

- In developer tools, you can hover over elements to see their HTML

This is how you find the HTML selectors needed for your scraper

In Chrome/Firefox developer tools, click the element picker icon (cursor in box) then click any element on the page. The HTML for that element will be highlighted in the developer panel.

Example: A Simple Web Page

2c.4 Basic Scraping Techniques

Now comes the practical part: actually writing code to extract data. We'll start with the fundamentals and build up to more complex techniques. By the end of this section, you'll be able to fetch a web page, find the data you need, and extract it into a usable format.

🔍 Applying This to Our Project

For our CO2 emissions scraper, we need to: (1) fetch the page at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_carbon_dioxide_emissions, (2) locate the table with class wikitable, and (3) extract each row into a DataFrame. The code examples below show exactly how to do this.

We'll use Python with BeautifulSoup (most common) and R with rvest. Stata doesn't have native scraping capabilities, but you can call Python from Stata (not covered here, but you can ask the chatbot if you're interested!).

Step 1: Fetch the Page

The problem: Before you can extract data, you need to get the HTML content of the page into your program. This is like downloading the page's source code.

The solution: Use a library that sends HTTP requests (the same protocol your browser uses) and receives the HTML back.

# Python: Fetch a web page

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

# Define a User-Agent (identifies your scraper)

# Be honest - some sites block generic Python requests

headers = {

'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Research scraper for academic project; contact@university.edu)'

}

# Fetch the page

url = "https://example.com/data"

response = requests.get(url, headers=headers, timeout=30)

# Check if request was successful

if response.status_code == 200:

print("Success! Page fetched.")

# Parse the HTML

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, 'html.parser')

else:

print(f"Error: {response.status_code}")# R: Fetch a web page

library(rvest)

library(httr)

# Define User-Agent

set_config(user_agent("Research scraper for academic project; contact@university.edu"))

# Fetch and parse the page in one step

url <- "https://example.com/data"

page <- read_html(url)

# Page is now ready for extraction

print("Page fetched successfully")Step 2: Extract Data

# Python: Extract data from HTML

# Find a single element

title = soup.find('h1')

print(f"Title: {title.text}")

# Find by class name

price = soup.find('span', class_='price')

# Find by id

main_content = soup.find(id='main-content')

# Find ALL matching elements

all_prices = soup.find_all('span', class_='price')

for p in all_prices:

print(p.text)

# Extract from a table

table = soup.find('table', class_='data-table')

rows = table.find_all('tr')

for row in rows[1:]: # Skip header row

cells = row.find_all('td')

country = cells[0].text.strip()

gdp = cells[1].text.strip()

print(f"{country}: {gdp}")

# Extract attribute values (like href from links)

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

href = link.get('href')

print(href)# R: Extract data from HTML using rvest

# Find elements using CSS selectors

title <- page %>%

html_element("h1") %>%

html_text()

print(paste("Title:", title))

# Find by class (use . prefix for class)

prices <- page %>%

html_elements(".price") %>%

html_text()

# Find by id (use # prefix)

main_content <- page %>%

html_element("#main-content") %>%

html_text()

# Extract a table (rvest makes this easy!)

table_data <- page %>%

html_element("table.data-table") %>%

html_table()

print(table_data)

# Extract attribute values (like href)

links <- page %>%

html_elements("a") %>%

html_attr("href")

print(links)CSS Selectors Quick Reference

| Selector | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

tag |

Element by tag name | div, table, a |

.class |

Element by class | .price, .data-table |

#id |

Element by id | #main-content |

tag.class |

Tag with specific class | span.price |

parent child |

Nested elements | table tr td |

[attr=value] |

By attribute | [data-country="USA"] |

2c.5 Advanced Techniques

The basic techniques work great for simple pages. But real-world scraping often hits complications. In this section, we'll tackle the common challenges you'll encounter and show you how to solve them.

🔍 Beyond Our CO2 Example: Real-World Challenges

Our Wikipedia example is intentionally simple. In real research projects, you'll face additional challenges:

- Pagination: Data spread across multiple pages (e.g., search results showing "Page 1 of 50")

- Dynamic content: Modern sites load data with JavaScript—your basic scraper sees an empty page

- Rate limiting: Hitting a server too fast will get your IP blocked

- Authentication: Some data requires login (not covered here—ask the chatbot if you need this)

Handling Pagination

The problem: You've successfully scraped the first page of results, but the website shows "Page 1 of 10"—the data you need is spread across multiple pages.

Why this happens: Websites break large datasets into pages to improve load times and user experience. A municipal budget might list hundreds of line items across dozens of pages.

The solution: Write a loop that visits each page in sequence, extracting data from each one and combining the results.

# Python: Handle pagination

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import time

# Store all results

all_data = []

# Loop through pages

for page_num in range(1, 11): # Pages 1-10

url = f"https://example.com/data?page={page_num}"

# Be polite: wait between requests

time.sleep(2) # Wait 2 seconds

response = requests.get(url, headers=headers)

if response.status_code != 200:

print(f"Error on page {page_num}, stopping")

break

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, 'html.parser')

# Extract data from this page

items = soup.find_all('div', class_='item')

# Check if page is empty (end of data)

if not items:

print(f"No more data after page {page_num-1}")

break

for item in items:

all_data.append({

'name': item.find('h2').text,

'value': item.find('span', class_='value').text

})

print(f"Page {page_num}: {len(items)} items")

print(f"Total: {len(all_data)} items collected")# R: Handle pagination

library(rvest)

library(purrr)

# Function to scrape one page

scrape_page <- function(page_num) {

# Be polite: wait between requests

Sys.sleep(2)

url <- paste0("https://example.com/data?page=", page_num)

page <- read_html(url)

# Extract table or items

page %>%

html_element("table.data-table") %>%

html_table()

}

# Scrape pages 1-10

all_data <- map_dfr(1:10, scrape_page)

print(paste("Total rows collected:", nrow(all_data)))Handling Dynamic Content (JavaScript)

The problem: You run your scraper but get an empty result—or the HTML you receive doesn't contain the data you can clearly see on the page. What's happening?

Why this happens: Modern websites often load data after the initial page loads, using JavaScript. When you visit the page in a browser, JavaScript runs and fetches the data. But when your scraper fetches the page, it only gets the initial HTML—before JavaScript has run. The data simply isn't there yet.

How to diagnose this: In your browser, right-click and select "View Page Source" (not "Inspect"). If you can't find your data in the source but you can see it on the rendered page, JavaScript is loading it dynamically.

You have three options, in order of preference:

- Find the hidden API: Open Developer Tools → Network tab → reload the page → look for XHR/Fetch requests. The data often comes from a JSON API that's much easier to scrape directly!

- Use Selenium/Playwright: These tools control a real browser that executes JavaScript. More complex, but works for any site.

- Check for a static version: Some sites offer non-JS versions for accessibility or older browsers.

# Python: Handle JavaScript with Selenium

# First: pip install selenium webdriver-manager

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.service import Service

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from selenium.webdriver.support.ui import WebDriverWait

from selenium.webdriver.support import expected_conditions as EC

from webdriver_manager.chrome import ChromeDriverManager

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

# Set up Chrome in headless mode (no visible window)

options = webdriver.ChromeOptions()

options.add_argument('--headless')

driver = webdriver.Chrome(

service=Service(ChromeDriverManager().install()),

options=options

)

try:

# Load the page

driver.get("https://example.com/dynamic-data")

# Wait for specific element to load (max 10 seconds)

wait = WebDriverWait(driver, 10)

wait.until(EC.presence_of_element_located((By.CLASS_NAME, "data-table")))

# Now page is fully loaded - get the HTML

html = driver.page_source

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

# Extract data as usual

table = soup.find('table', class_='data-table')

print("Data extracted successfully!")

finally:

# Always close the browser

driver.quit()2c.6 Best Practices for Research

You now know how to scrape. This section is about how to scrape responsibly—both for ethical reasons and practical ones. A well-designed scraper is more likely to succeed and less likely to get you in trouble.

🔍 Applying This to Our Project

For our CO2 emissions scraper, best practices mean: (1) adding a 1-2 second delay between requests if scraping multiple pages, (2) setting a User-Agent that identifies our scraper, (3) caching pages locally so we don't re-download during development, and (4) handling errors gracefully if Wikipedia is temporarily unavailable.

The Gentleman-Scraper's Checklist

- Identify yourself: Use a clear User-Agent with contact info

- Respect robots.txt: Don't access disallowed pages

- Rate limit: Add delays (2+ seconds) between requests

- Cache responses: Don't re-fetch pages you've already downloaded

- Handle errors gracefully: Don't hammer a server if it returns errors

- Scrape during off-hours: Minimize impact on the server

- Only take what you need: Don't download entire websites

- Store data securely: Especially if it contains personal information

- Document your methodology: For reproducibility and ethics review

- Consider reaching out: Website owners may provide data directly

Rate Limiting and Caching

These two techniques solve different problems, but they're both essential for any serious scraping project.

🚦 Rate Limiting: Why You Need It

The problem: Your scraper can request pages much faster than a human would—potentially hundreds per second. This can overwhelm the server, slow down the website for other users, or trigger security measures that block you.

The solution: Add a deliberate delay between requests. A 2-3 second delay is polite. Some sites specify a Crawl-delay in their robots.txt—always respect it.

💾 Caching: Why You Need It

The problem: While developing your scraper, you'll run it many times—testing, fixing bugs, adjusting selectors. Each run re-downloads pages you already have, wasting time and putting unnecessary load on the server.

The solution: Save each page's HTML to a local file. Before fetching a URL, check if you already have it cached. This makes development faster and reduces server load.

Bonus benefit: If your scraper crashes halfway through, you don't lose progress—cached pages don't need to be re-downloaded.

# Python: Polite scraping with rate limiting and caching

import requests

import time

import hashlib

import os

from pathlib import Path

class PoliteScraper:

def __init__(self, delay=2, cache_dir="scraper_cache"):

self.delay = delay

self.cache_dir = Path(cache_dir)

self.cache_dir.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

self.last_request = 0

self.session = requests.Session()

self.session.headers.update({

'User-Agent': 'Research Scraper (contact@university.edu)'

})

def _get_cache_path(self, url):

# Create unique filename from URL

url_hash = hashlib.md5(url.encode()).hexdigest()

return self.cache_dir / f"{url_hash}.html"

def fetch(self, url, use_cache=True):

cache_path = self._get_cache_path(url)

# Check cache first

if use_cache and cache_path.exists():

print(f"Using cached version of {url}")

return cache_path.read_text()

# Rate limiting

elapsed = time.time() - self.last_request

if elapsed < self.delay:

time.sleep(self.delay - elapsed)

# Make request

response = self.session.get(url, timeout=30)

self.last_request = time.time()

if response.status_code == 200:

# Cache the response

cache_path.write_text(response.text)

return response.text

else:

raise Exception(f"HTTP {response.status_code}")

# Usage

scraper = PoliteScraper(delay=3)

html = scraper.fetch("https://example.com/page1")

html = scraper.fetch("https://example.com/page2")Error Handling and Retries

The problem: When scraping 200+ sites, things will go wrong. Servers will be temporarily unavailable, your internet connection will hiccup, some pages will return errors. If your scraper crashes at error #50, you lose all progress.

The solution: Build resilience into your scraper. When a request fails, wait and try again (this is called "retrying with exponential backoff"). Only give up after multiple failures.

Instead of retrying immediately (which might fail again), you wait progressively longer: 5 seconds, then 10 seconds, then 20 seconds. This gives the server time to recover and avoids hammering it when it's already struggling.

# Python: Robust error handling

import requests

import time

from requests.exceptions import RequestException

def fetch_with_retry(url, max_retries=3, base_delay=5):

"""Fetch URL with exponential backoff on failure."""

for attempt in range(max_retries):

try:

response = requests.get(url, timeout=30)

# Success

if response.status_code == 200:

return response.text

# Rate limited - wait and retry

elif response.status_code == 429:

wait_time = int(response.headers.get('Retry-After', base_delay))

print(f"Rate limited. Waiting {wait_time}s...")

time.sleep(wait_time)

# Server error - wait and retry

elif response.status_code >= 500:

delay = base_delay * (2 ** attempt)

print(f"Server error. Retry in {delay}s...")

time.sleep(delay)

# Client error - don't retry

else:

raise Exception(f"HTTP {response.status_code}")

except RequestException as e:

print(f"Request failed: {e}")

if attempt < max_retries - 1:

delay = base_delay * (2 ** attempt)

print(f"Retrying in {delay}s...")

time.sleep(delay)

raise Exception(f"Failed after {max_retries} attempts")

# Usage

html = fetch_with_retry("https://example.com/data")When scraping large amounts of data, save to disk after each page. If your script crashes after 2 hours, you don't want to lose everything. Use caching (shown above) or append to a CSV/database as you go.

🛠️ Troubleshooting: Common Problems & Solutions

Here's a quick reference for problems you'll likely encounter. Bookmark this section!

❌ "My scraper returns empty results"

Likely cause: JavaScript is loading the content. Fix: Check if View Page Source shows the data. If not, use Selenium or find the underlying API in the Network tab.

❌ "I'm getting blocked (403 Forbidden)"

Likely cause: You're hitting the server too fast, or missing a User-Agent header. Fix: Add longer delays (5+ seconds), set a proper User-Agent, and respect robots.txt.

❌ "My selector worked yesterday but fails today"

Likely cause: The website changed its HTML structure. Fix: Re-inspect the page and update your selectors. This is why scraping requires ongoing maintenance.

❌ "I'm getting encoding errors (weird characters)"

Likely cause: Character encoding mismatch. Fix: Check the page's encoding in the response headers or meta tag. Use response.encoding = 'utf-8' (Python) before accessing response.text.

❌ "My scraper works but is painfully slow"

Likely cause: You're re-downloading pages unnecessarily. Fix: Implement caching! Also consider if you really need every page—maybe you can sample or prioritize.